Why Perfect Tools Make Imperfect Humans

How frictionless design robs us of the struggle that builds understanding

The first time you tie a bowline knot, your fingers become strangers to themselves. The rope rebels. Your hands cramp into shapes they've never made.

You watch someone else's fingers dance the familiar pattern they loop, thread, pull and yours on the other hand respond with the grace of frozen sausages.

But somewhere between the fifteenth and fiftieth attempt, something shifts.

The rope begins to speak. Your fingers learn its language. And in that learning, you discover something modern interfaces have made us forget: that struggle is a form of seeing.

We live in an age of frictionless design. Our tools optimize themselves to our habits before we know we have them.

Spotify learns our taste faster than we do.

Gmail finishes our sentences.

Our phones unlock by recognizing the specific geography of our faces.

Everything bends to us, molds around us, anticipates us. We've built a world that never makes us foreigners to our own fingers.

And that's precisely what we've lost.

Consider the photographer in a darkroom, hands submerged in developer liquid, feeling for the edge of paper in absolute darkness.

She cannot see her work; she must imagine it through touch, time it through breath.

Every film demands a physical interaction, keep it too long and the shadows mud, keep too short and the highlights blow. She becomes the light meter. Her lungs becomes, a clock.¹

Now for a second think of Instagram's one-tap filters. Valencia. Mayfair. Ludwig. Each filter packages ten thousand hours someone spent learning how light actually behaves and templates it.

The manual transmission offers us another lens. Every driver who learned on a stick shift gear, carries the muscle memory of failure, they instinctively “get” the shudder of a stalling engine, the smell of burning clutch, the specific humiliation of rolling backward on a hill while someone honks behind you.

But they also carry something else: an embodied understanding of how power transfers through metal, how momentum builds and breaks. They know the car as a physical system, not a service.

Today's CVT transmissions optimize themselves in real-time. They find the perfect gear ratio without human input, without human error, without human understanding.

Smooth as silk. Dead as data.

Even tho you might feel it’s my nostalgia speaking, I’d argue this is neuroscience.

When we struggle with a tool, our mirror neurons fire differently. We don't just learn the task; we learn the teacher.

Medieval apprentices didn't simply learn techniques from their masters. By watching hands shape clay for seven years, they absorbed something deeper:

how to move with deliberation,

how to read wood grain before cutting,

how to wait for iron to reach the right color.

The clumsiness was the curriculum. The inefficiency was the education.²

Modern software tutorials, by contrast, teach us to be efficient operators, not empathetic practitioners.

We learn the shortest path, not the terrain.

We memorize keyboard shortcuts without understanding why certain functions live where they do, what metaphors shaped their logic, what human decided that "save" should live under "file" and not "edit."

A chef teaching knife skills doesn't start you on a food processor. She hands you a dull knife and an onion.

You cry from the vapors, from the frustration, from the micro-cuts that teach you where your fingers end and the blade begins. Slowly, you learn the onion's grain, its layers' resistance, the specific sound it makes when cut correctly.

The dull knife teaches you pressure.

The tears teach you angle.

The slow prep teaches you that efficiency is earned, not downloaded.

Now we have meal kit services delivering pre-chopped vegetables in perfect portions. AI recipe generators that know your allergies but can't tell you why ginger wakes up carrots or why salt makes chocolate sing.

The efficiency is impressive. The education is absent.

We're raising a generation on tools that never push back.

The implications cascade through every domain.

We rush to give students AI tutors that adapt perfectly to their learning style, forgetting that struggling against a mismatched teaching method builds intellectual flexibility.

We auto-tune imperfection away, forgetting that hearing your own bad pitch develops your ear.

We GPS our way everywhere, forgetting that getting lost teaches us to see.

The word "empathy" comes from the German *Einfühlung*: "feeling into." It originally described how observers project themselves into artworks, how we physically mirror what we see.

But you cannot feel into something that never resists your touch. You cannot empathize with a system that shapes itself perfectly around you.

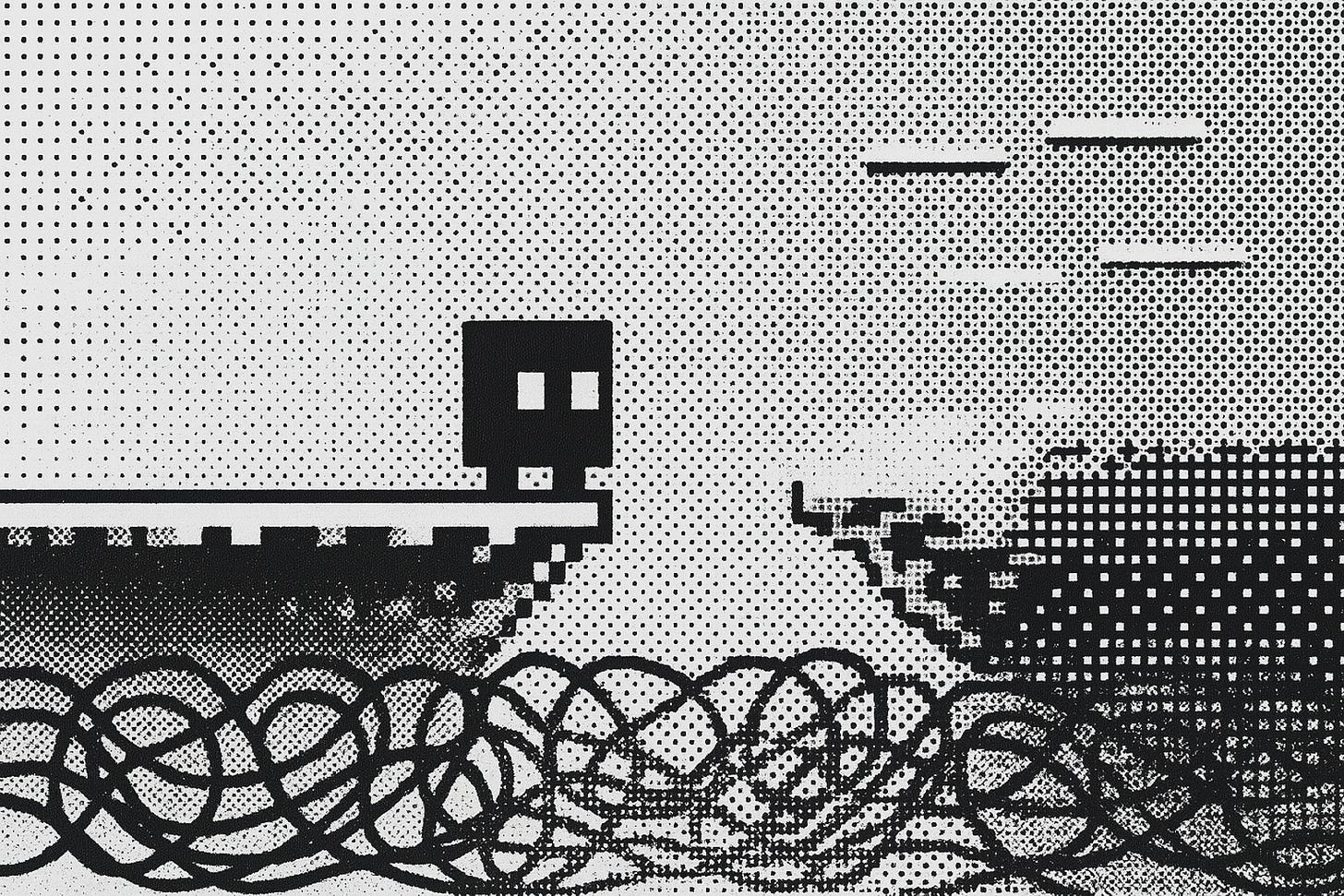

This is the paradox of perfect tools: they make us weaker users.

So here's my provocation for designers, educators, anyone who shapes tools that shape people:

Add empathy latency back into your systems.

Build in what I call "teaching friction": moments where the tool requires users to meet it halfway.

Make your onboarding occasionally obtuse. Let your interface sometimes speak its own logic rather than anticipating user logic.

Create what gamers would recognize as a skill curve, where mastery means understanding the system's language, not just its outputs.

Duolingo almost gets this right with its deliberately repetitive exercises, but it optimizes too quickly to your errors.

Better would be an app that occasionally insists on its own pedagogical rhythm, that makes you slow down when you want to speed up, that teaches patience as a prerequisite to progress.

For AI systems, this might mean copilots that occasionally refuse to complete a task, instead walking users through the why.

"I could write this function for you,"

the system might say, "but let's build it together so you understand what each line does."

Yes, it's inefficient. That's the point.

For physical products, it means resisting the urge to hide all complexity. The most beloved tools teach through use.

Swiss Army knives reveal their logic through fumbling.

Cast iron pans wear in specific patterns that tell stories.

They require maintenance rituals that build relationships. They improve with age and attention, not despite it.

The bowline knot still teaches what no quick-release carabiner can: that security comes from understanding forces, not trusting mechanisms.

That the rope has wisdom your fingers must learn. That becoming fluent in any system requires first being clumsy in it.

We've spent decades building tools that speak our language perfectly. Maybe it's time to build tools that teach us theirs.

The future doesn't need more frictionless interfaces.

It needs more teachers disguised as tools.

It needs products that make us students again, that return us to beginner's mind, that remind us that mastery isn't about bending the world to our will. It's about learning to work with resistance, not against it.

Your fingers remember every knot they've learned to tie. What will they remember of tomorrow's tools?

¹ The darkroom timer's tick becomes a heartbeat. Ansel Adams spoke of "visualizing" the final print before ever touching paper, this is a mental model built through thousands of failed attempts. Digital photography's instant feedback loop trades this deep visualization for iterative correction. We shoot a hundred versions instead of imagining one.

² Medieval guilds required seven years of apprenticeship not because techniques took that long to learn, but because becoming required that much watching, failing, absorbing. The inefficiency was a feature: it selected for dedication and ensured knowledge transferred with context, not just content

This is the first dispatch from Texture of Tomorrow, where I examine the intersection of technology and human experience to find patterns worth understanding.

If this piece resonated, consider sharing it with someone who might value the perspective.